The late winter season of 1885 in

Hamilton had been tough in terms of prolonged cold temperatures and plenty of

snow. By the middle of March, when everyone’s thoughts were turning towards

what they hoped was an impending arrival of spring, Hamilton still was in the

grip of winter.

On March 12, 1885, both Hamilton

newspapers were informed that one of the city’s leading citizens Mr. William

Hendrie had some news winter sports enthusiasts :

“Mr. William Hendrie, who has always been a thorough patron and advocate

of all legitimate sports and pastimes for sports’ sake, has introduced a

capital precedent and opened his spacious grounds (Homestead) to the public,

that they may enjoy that good old form of Canadian outdoor winter amusement,

bob-sleigh coasting.”1

1 “Mr. Hendrie Caters to Coasters”

Hamilton Times. March 12, 1885.

The Hendrie mansion, and its

extensive grounds occupied the full block, Macnab to Park streets, Duke to Bold

streets. The main entrance for carriages into Holmsted was from Bold street,

opposite the southernmost end of Charles street.

The Times described the scene on

Charles street, running north from the grounds of Holmsted, during the first

night of coasting after the announcement from Mr. Hendrie :

“ About 200 people, equipped with

at least 80 trim-built and speedy-looking bobs, kept Charles street in a very

merry mood from 7 to 10 last night. Mr. Hendrie had several strong reflecting

lights placed at intervals along the coasting line, and over the large front

gates, through which the coasters passed, was an arch formed of Chinese

lanterns. A number were also hung among the shrubbery, the whole looking very

picturesque.

“During the evening, large

numbers of spectators visited the slide, drawn thither by the numerous horns,

bells, flashing lights and attractive illuminations. Mr. Hendrie very kindly

extends these privileges as long as the good weather and slipping permits.”1

The night-time coasting

experience along the brightly-lighted street from the Holmsted all the way to King

street was a delight. Every evening large number of young people, and a few

older types, were enjoying the thrill of speeding down the hill, with lights on

the track. In the Spectator’s Diurnal Epitome column of March 16, 1885 noted

the fun that was happening at the location:

“Coasters

had a gala time on the Charles street hill Saturday night. The street from Mr.

Hendrie’s house to Main street was a blaze of light, a large headlight at Mr.

Hendrie’s residence and numerous lesser lights as well as light at Mr.

Gillespie’s residence making the scene one of brilliancy and animation that was

well worth beholding. The many coasters’ hearts

were full of joy, and they keenly appreciated the generosity of their

kind-hearted benefactors.”2

2 “The

Diurnal Epitome : What Goeth In and About the City : Items of Local News

Gathered By Spectator Reporters And Presented in Attractive Form for the

Interested Reader. ”

Hamilton

Spectator March 16, 1885.

Unfortunately

the joy of the coasting slide can to an abrupt end Wednesday evening, March 16,

1885:

“For the past ten days, Mr.

Hendrie has opened his grounds to the young people who patronized the

bobsleighs, and scores of heavy loads have gone whizzing down the hill gaining

fresh impetus at every travelled yard. Last night fully two hundred people were

thus engaged, and the slide was full of sleighs”3

When a line of coasters was

already underway heading down the Charles street hill, a carter’s lorry, driven

by Robert McQuillan was seen driving eastward along Hunter street:

“Mr. Waddell, Mr. Burrows and

Chief Stewart, seeing that a frightful collision was imminent, called to him to

stop, the latter gentleman going in front of the horse to prevent its progress.

McQuillan, however, deliberately drove on and a bob with six persons on it came

crashing into its wheels. The force of the collision threw the driver to the

off, and the occupants of the sleigh were scattered senseless on the ground.”3

3 "Coasting Disaster : Collision of a ‘Bob’ With a

Lorry Last night : Three Persons Seriously Hurt”

Weekly Times. March 19, 1885.

A reporter for the Hamilton

Spectator had been at the Charles street hill and witnessed the incident

firsthand:

“All

went well until about half-past 8, when the accident occurred, which summarily

stopped the coasting for the night.

“All the bob sleighs went down

the incline together, a procession of some 40 or 50 bobs, each carrying from 3

to 7 persons. As the head of the line approached Hunter street, the crowd on

the corner saw a horse and lorry coming east at a brisk pace along Hunter

street, and several persons raised a warning cry to the driver, but that person

either did not hear or heed the cry and pressed on. The danger now became

apparent to everyone who saw the situation.

“Chief Stewart, who was in the

crowd, ran out into the road and held up his hands in front of the horse; but

the driver urged the animal on until it ran against the chief, who stepped

aside to save himself, and the horse and cart passed on.

“By this time the leading bob in

the line had reached the corner. It was steered by one of Mr. Hendrie’s sons,

who had two ladies behind him. He saw the danger in time to steer out of the

way, but almost grazed the lorry in flying past.

“On the second bob were half a

dozen persons. It was steered by Mr. Wm. Moore, of 134 main street east, and

immediately behind him sat Miss Isabel and Miss Beatrice Burrows, daughters of

John C. Burrows, of 36 Hunter street west. Mr. Moore did not see the danger in

time to avert it, and his bob crashed into the rear wheel of the lorry.

“The coasters were hurled to the ground or

against the lorry, and the force of the collision was so great that the lorry

was driven half way round and the driver was thrown to the ground. The horse

proceeded on its way down Hunter street, and the driver picked himself up and

ran after it without troubling himself about the unfortunate coasters, who were

all stunned, and lay prostrate on the ground.

“All but three, however, were

able to rise and walk away, though none of them escaped without bruises.

“The three who were seriously

injured were Mr. Moore and Misses Burrows. Fortunately for the gentleman, he

had instinctively thrust his feet before him and thus broke the force of the

collision; if it had not been for this, he would have been killed. As it was,

his face was dashed against the hub of the wheel and was terribly cut and

bruised.

“Miss Beatrice Burrows was also

thrown against the wheel, and her sister against the side of the lorry. The

former was carried to her home nearby, and her sister and Mr. Moore were borne

to R. R. Waddell’s house, where their injuries were attended to by Dr. Husband

and Dr. Bingham. They were conveyed home later in the evening.

“Mr. Moore’s head and face are so

badly cut and bruised that he is likely to be disfigured for life. Miss Isabel

Burrows, who is a teacher in the Central school, is not cut, but received

several painful bruises on the body as well as on her head and face. Miss

Beatrice Burrows’ injuries are more serious. Her nose was broken and her face

gashed and bruised cruelly. She also had a hip so severely strained that it may

prove troublesome.”4

4 "Serious Coasting Accident : Three Persons Badly Injured By a

Collision on Charles Street”

Hamilton Spectator March 17, 1885.

The carter, McQuillan, made no

effort to stop and see what had happened, but continued to drive away:

“Immediately after the accident,

Chief Stewart and Constable Johnston went in search of the carter who was

mainly responsible for the accident. His name is Robert McQuillan. He was found

at his father’s house, 110 West avenue north, and arrested on a charge of

malicious injury. He was drunk when taken into custody, and so far from

expressing regret at what had occurred, he stoutly declared that he had a

greater right to the road than the coasters had.”4

McQuillan spent the night in the police

cells and was brought before Magistrate Cahill the next day:

“At the Police Court this

morning, McQuillan’s name was entered opposite a charge of malicious injury to

persons. Chief Stewart said that the injured persons were not able to appear

and he would have to ask for an adjournment.

“Mr.

Sadlier appeared for the defence. He said ; ‘McQuillan was driving along the

public street, as he had lawful rights to do, and those who are injured ran

into him. It would have been the act of a humane man to stop when he was told,

but I doubt very much if he is criminally responsible. He didn’t run into them.

They ran into him. I have no objection to an adjournment.’

“Constable

Johnston was called and said that McQuillan had been warned not to cross

Charles street.

“Chief

Stewart pointed out that McQuillan was not in charge of his horse when the

animal first appeared. It crossed Hunter street and was taken in charge by two

boys, who brought it back to Mr. Waddell’s house, and it was tied up there.

When McQuillan came along he got in and wheeled around, driving east on Hunter street. Mr.

Waddell, Mr. Burrows and the Chief warned him of the danger, and the Chief

attempted to stop his horse, but McQuillan drove the animal against him.

“McQuillan

said that the horse had been tied in front of a house on Hunter street, and had

got away by breaking the line by which it was fastened. When he found it at Mr.

Waddell’s and got in the wagon he could not stop the horse, on account of

having but one line. He did not see the coasters until the first sleigh had

passed him, and then he shouted to the horse, hoping to get out of their way.

He denied being drunk and said he had not taken any liquor.”3

McQuillan

was not granted bail immediately and had to spend another two nights in jail

before he was released. It was decided to sent case to a higher court to be

tried at the upcoming spring assizes.

As for coasting along Charles

street, that experience had come to an end:

“The coasters’ slide on Charles

street was not like a private toboggan slide. It was open to all comers, and

was patronized by people not only from the immediate vicinity, but from all

parts of the city. Mr. Wm. Hendrie, whose residence, Holmstead, is at the head

of the street, had very kindly thrown open his grounds and illuminated the

slide with locomotive headlights. He was quite willing that coasters should

have the use of his property to make the slide complete, but he did not wish to

interfere with any person doing business on the streets, and as soon as he

found that McQuillan thought his rights were interfered with by the maintenance

of the slide, it was closed and the lights extinguished.

“There

is not likely to be any more coasting on Charles street.”3

Police Chief Stewart came to a decision unilaterally that coasting on

public streets was too dangerous to allow it to be continued:

“It is likely that this accident

will have the effect of putting a stop to coasting in this city – at least on

Charles street. Chief Stewart said last night that he would endeavor to prevent

it in this locality during the remainder of the season.”4

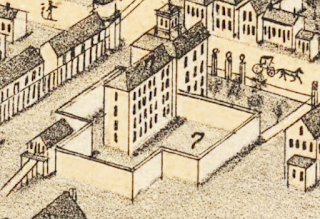

Above, top, detail from 1876 Bird's Eye View map, below an undated photo of Holmsted.